In December 1950, President Truman announced that he was sending approximately 70,000 American troops to Europe in support of the North Atlantic Treaty.[1] Truman claimed that Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty granted him the authority to take such action.[2] These would be the first American ground forces placed in between the American-allied North Atlantic Treaty Organization (“NATO”) nations and the Soviet Bloc, an otherwise peaceful area of the world devoid of explicit and overt military threats at the time.[3]

Domestically, Truman’s announcement prompted a significant foreign policy and constitutional authority debate among members of the federal government. Known as the “Great Debate,” members of Congress, the executive branch, and former presidents argued over the larger question of presidential versus congressional authority under the constitutional war powers.[4] Key to this debate was the fact that the President had announced an international troop deployment without seeking approval or input from Congress.[5] When asked in a press conference whether he thought he needed congressional authorization to send troops to Europe, President Truman plainly responded, “No, I do not.”[6] Truman further stated in another press conference that he did not need permission from Congress to deploy troops in this manner.[7]

For three months, Congress debated over whether the president had the power to send troops abroad without their approval. Members of Congress contemplated the Constitution’s division of the war powers between the executive and legislative branches, a novel issue in the post-World War II American political landscape. But the “Great Debate” was not exclusive to the halls of Congress. Former-President Herbert Hoover made a speech on December 20, 1950 in which he condemned Truman’s unilateral decision to send troops to Europe.[8] Among his stated reasons, Hoover thought it more prudent to wait for U.S. allied European nations to commit troops to protecting peace in their own region before committing American troops to stand between them and the Soviet Bloc.[9] On January 5, 1951, Senator Robert Taft made a 10,000 word speech in the Senate in opposition to Truman’s unilateral troop deployment, echoing many of former-President Hoover’s sentiments.[10] Senator Taft rejected President Truman’s belief that Article 3 empowered him to take such action.[11] Instead, the Senator argued that Truman did not possess constitutional authority and must therefore obtain approval from Congress to properly deploy troops abroad.[12]

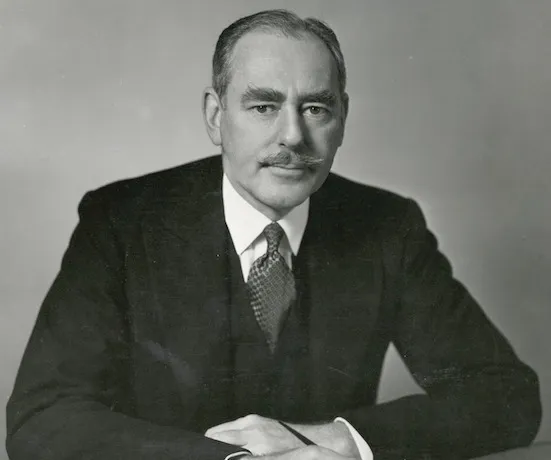

Note, however, that these events took place before the Supreme Court’s decision in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co., v. Sawyer (1952).[13] To that end, the “Great Debate” in the Senate primarily centered around the passage of Senate Resolution 8 (“S.R. 8”), a nonbinding resolution which begrudgingly approved President Truman’s deployment of ground forces to the European area and attempted to limit the president’s ability to send additional troops in the matter.[14] The Senate called Secretary of State Dean Acheson [photograph above] before the Senate Committees on Foreign Affairs and Armed Forces in connection with S.R. 8 as a representative of the State Department and, more importantly, the executive branch’s position regarding the announced troop deployment and the president’s perceived authority to take such action.[15]

The questions and arguments contemplated throughout the “Great Debate” are taken for granted in modern America—we merely assume the president has the power as Commander-in-Chief to send troops wherever and whenever he decides. However, reexamining the “Great Debate” from the perspective of the executive branch can help us to better understand why we now believe that the president possesses constitutional authority to unilaterally deploy troops in times of peace. Furthermore, a reexamination of the “Great Debate” offers an insight into constitutional arguments about the president’s role in the constitutional war powers that persist to this day.

In this paper, we will focus on the executive branch’s arguments, particularly those of Secretary of State Dean Acheson, during the “Great Debate” in support of presidential authority. In Part 1, we will briefly summarize the historical context of post-World War II America and the contemporary international political climate. Most significant to this background are mutual security agreements that precipitated President Truman’s decision in 1950 to send U.S. troops to Europe. In Part II, we will discuss the proposal and passage of S.R. 8 and its impact on the division of the constitutional war powers in the Cold War era. Finally, and most importantly, Part III will examine Secretary of State Dean Acheson’s arguments in support of presidential authority to unilaterally deploy troops during peacetime. Ultimately, I aim to dissect the arguments in favor of presidential authority during the “Great Debate,” many of which reflect present sentiments regarding the same.

- Background and Contemporary Context

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the international landscape and the United States’ position in it appeared drastically different than in previous history. The starkest changes occurred within the U.S. economy and foreign and military policies. Prior to the Second World War, the United States had an economy slowly re-emerging from the ravages of the Great Depression. At the same time, the U.S. possessed a nominal standing army (by today’s standards), and a foreign policy strategy founded on isolationism.[16] In fact, for most of its history, the United States relied on its natural, physical separation from Europe and Asia so as to avoid entangling alliances and other forms of international conflicts.[17]

However, the United States was forced to reconsider its traditional foreign policy stances in the aftermath of World War II. The U.S., unlike other major world powers, emerged from this devastating international conflict with an economy “three times the size of the next competitor.”[18] By 1945, U.S. military spending was nearly three times higher than the other major world powers combined.[19] The U.S. emerged from the war with weapons superiority, in part because it was the only nation in possession of the nuclear bomb. The United States added to its military superiority in the late 1940s when it retained over 600,000 active-duty military personnel, which was four times larger than the standing military of the 1920s and 1930s.[20] President Truman increased this standing military force to more than 1.5 million troops by the Spring of 1950, with plans for further expansion in the near future.[21] Thus, its economy and military positions established post-war America as a global hegemon primed to preserve and protect the hard-fought international peace from the threat of communism—namely, the ever-expanding influence of the Soviet Union and Maoist China.

Mutual defense treaties and pacts played a key role in this national foreign policy shift. Congress voted to ratify the Charter of the United Nations in 1945, officially committing the United States as both a general member and a member of the U.N. Security Council.[22] In 1949, the U.S. signed the North Atlantic Treaty, joining Canada and ten European countries in NATO.[23] These mutual security agreements and alliances turned the political calculus of American foreign relations and military decision-making on its head.[24] The U.S. was no longer content to sit by and hide behind its natural separation from the powder keg of Europe and international conflicts. As Secretary of State Acheson explained to the Senate in 1951, continuing the inter-war period policy of neutralism was “a short cut to suicide.”[25] By signing these agreements, the Truman Administration dedicated America to taking a more active role on the world stage.[26]

When ratifying these mutual defense pacts, though, Congress faced the challenge of preserving the constitutional division of powers, especially the war powers. For example, Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty required that each member nation “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.”[27] Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty stated:

“The parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all; and consequently, they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defense recognized by article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the party or parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other parties such action as it deems necessary, including the use of the armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic Area.”[28]

Note that Article 5 expressly permitted signatories to take any military and defensive action permitted under Article 51 of the U.N. Charter.[29]

Congress feared that such language would allow the president to unilaterally enter the United States into a war or institute military action, thereby abrogating Congress’ exclusive authority to declare war.[30] To prevent such an infringement of the congressional war powers, the Senate inserted language into both the U.N. Charter and the North Atlantic Treaty that would require each signatory country to carry out the provisions of the treaty “in accordance with their respective constitutional processes.”[31] Secretary of State Acheson also assured Congress during a hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee regarding the North Atlantic Treaty that Article 5 would not automatically pull America into war if another signatory nation were attacked.[32] The Secretary told senators, “Under our Constitution, the Congress alone has the power to declare war.”[33] When asked directly if an attack on one NATO country would immediately require the United States to declare war on the attacking nation, Secretary of State Acheson replied, “Unequivocally ‘No.’”[34] As a result, the Senate ratified the North Atlantic Treaty on the belief that, on its own, this treaty could not bind the U.S. to enter or start a war; rather that power remained specifically and exclusively within the purview of the House of Representatives. Note, however, that the Senate did not contemplate in connection with the North Atlantic Treaty whether the president could send troops in times of peace to other NATO countries to preserve the treaty’s integrity.

The first major challenges to these mutual security pacts came in the form of two separate troop deployments by President Harry Truman announced in 1950, the first to Korea and the second to Europe. While the deployment to Europe is the focus of this paper and the “Great Debate” more broadly, the deployment to Korea occurred first and primed Congress for their skepticism of presidential authority under the war powers. To that end, we will discuss the Korean conflict briefly.

In June 1950, President Truman announced he was deploying U.S. troops to the Korean Peninsula.[35] The president declared this deployment without first seeking or obtaining approval from Congress. Although they voiced their opposition to the president’s decision to send troops and their skepticism regarding his constitutional authority to make such a decision without approval from the Legislative Branch, Congress continued to appropriate money to the military throughout the Korean conflict.[36] Thus, regardless of Congress’ arguments and rhetoric to the contrary, these legislators tacitly approved the president’s decision to send troops to Korea through their budget appropriations. Note that President Truman did not expressly rely on the Commander-in-Chief power to justify sending these troops abroad. Rather, he cited various resolutions passed by the U.N. Security Council as granting him the authority to do so.[37] Note also that these troops were deployed to repel an active military incursion into South Korea by a foreign, adversarial nation.[38]

While the President possessed dubious constitutional authority when sending troops to Korea, the second deployment announced in 1950 presented a novel question under the division of the war powers under the constitution. In December 1950, President Truman announced he was sending approximately 70,000 U.S. troops to Europe in furtherance of the North Atlantic Treaty.[39] This controversy formed the foundation for the “Great Debate,” in which Congress contemplated whether the president had the authority to send these troops abroad without first obtaining approval from the Legislative Branch. However, this situation also presented a new, broader constitutional question: “were there limits to the president’s power to station U.S. forces in peacetime on the territory of an ally?”[40] The Framers could not have contemplated this issue at the Constitutional Convention, nor had the country ever faced such a scenario, because of Framers’ and subsequent political leaders’ general aversion to entangling alliances. [41] The United States also lacked a sufficiently large standing military to carry out such an order for most of history.[42] Many in Congress believed that President Truman did not possess the authority alone to deploy these ground forces. The President begged to differ.

- Senate Resolution 8

In January 1951, Senate Minority Leader Kenneth Wherry of Nebraska introduced Senate Resolution 8 in response to President Truman’s December 1950 unilateral decision to send troops to Europe.[43] Also called the Wherry Resolution, S.R. 8 directly challenged the president’s authority to take such action without first receiving the express approval of Congress.[44] The resolution, as initially introduced, stated: “That it is the sense of the Senate, that no ground forces of the United States should be assigned to duty in the European area for the purpose of the North Atlantic Treaty pending the formulation of a policy with respect thereto by the Congress.”[45] After eleven days of public hearings regarding S.R. 8, the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees rewrote S.R. 8 in support of President Truman’s authority to send troops to Europe.[46]

Key to this final version of the Wherry Resolution was an amendment added by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas. The McClellan Amendment would require the President to seek congressional approval of any future plans to send troops in this matter.[47] The amendment stated that “no ground forces in addition to such four divisions should be sent to Western Europe in implementation of Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty without further congressional approval.”[48] While the Senate had agreed to approve President Truman’s initial troop deployment, they reserved to themselves the final say in whether more ground forces could be sent to Europe. The Senate adopted S.R. 8 on April 4, 1951 by a vote of 69 to 21.[49]

It is important to note that, as a resolution of only one legislative house, S.R. 8 was non-binding and did not have the force of law. Attempts to pass a binding joint resolution of both Houses of Congress failed.[50] Moreover, S.R. 8 was expressly limited in scope. Its language specifically and only contemplated President Truman’s ability to send troops to Europe in support of the North Atlantic Treaty.[51] Should the president wish to send more than the announced number of troops to the European area, S.R. 8 demanded that the president seek congressional approval prior to the deployment of those additional ground forces. However, even though S.R. 8 lacked the teeth necessary to hem in this type of presidential action, the resolution was never invoked.[52] President Truman did not send additional troops to Europe and thus did not challenge the Senate’s practically symbolic reprimand.[53]

Though non-binding, responding via a resolution granted senators the ability to debate “in substantial detail the boundaries of congressional and presidential power.”[54] It is important to note that there was no cohesive collective arguing in favor of inherent congressional authority in this matter during the “Great Debate.” The opposition side consisted of isolationists (who were committed to perpetuating the foreign policy practices of the pre-World War II era), lawmakers interested in preserving American freedom of action abroad (meaning anti-alliance lawmakers seeking to preserve the Framers’ aversion to entangling alliances), and lawmakers who supported the action but wanted increased troop commitments from European allies.[55] The “Great Debate” united these fundamentally different groups for the sole reason that they opposed President Truman’s actions and his justification for such actions. But because they opposed this action for different and inconsistent reasons, many of which were not grounded in fundamental constitutional arguments, the opposition’s arguments are not the focus of this paper.

Rather, we will examine the executive branch’s arguments made in response to the following question posed by Congress: from where did the president draw the authority to send troops abroad, to the soil of allied nations, without congressional authorization? Secretary of State Dean Acheson answered this and similar questions on behalf of the executive branch during his appearance before a joint hearing of the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Forces Committees regarding the Wherry Resolution.[56] It is these arguments, discussed below, which persist to this day in favor of presidential authority in the realm of troop deployments during times of peace.

- Secretary of State Acheson’s Constitutional Arguments on Behalf of the Executive Branch

In February 1951, the Senate Committees on Foreign Relations and Armed Services held eleven days of joint hearings regarding S.R. 8 (“the Joint Committee Hearing” or “the Joint Committee” or “the Hearing”).[57] Secretary of State Dean Acheson testified before the Joint Committee on February 16, 1951 as one of two representatives of the executive branch.[58] Chief among Acheson’s arguments, and of immediate concern to many senators participating in the Hearing, was whether President Truman possessed the authority to send troops abroad without first consulting Congress. Note, though, that the members of the Joint Committee asked Secretary Acheson about issues other than presidential authority in undertaking this troop deployment.[59] For example, many were concerned with the foreign policy considerations and implications underlying this decision.[60] Nevertheless, the question of presidential authority versus congressional authority loomed large in the Hearing, and it was one of the first issues addressed during the questioning period.[61] Note also that General of the Army Omar N. Bradley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, also testified before the Joint Committee regarding S.R. 8; his arguments are not within the scope of this paper.[62]

As a proponent of sending troops to Europe to foster the success of NATO, Secretary Acheson clearly articulated to the Joint Committee the executive branch’s understanding of the president’s constitutional authority—that the president could send troops and did not need approval from Congress at all. Acheson’s testimony before the Joint Committee can be broken into two parts: the Secretary’s opening statement to the Joint Committee and the questioning period. We will first examine Secretary Acheson’s arguments in his opening statement and then turn to examine the manner in which he answered questions from the senators on the Joint Committee about presidential authority.

In his opening statement to in the Joint Committee Hearing, Secretary Acheson did not address the issue of constitutional authority.[63] Instead, Acheson’s statement focused primarily on foreign policy arguments in support of Truman’s troop deployment as a preventative measure.[64] For example, the Secretary explained the central aim of the Truman Administration’s foreign policy in Europe as follows: “So our first purpose . . . is to deter the aggressors from attacking Europe. Our primary concern is not how to win a war after it gets started, but how to prevent it, and how to help Europe stay free in the meantime.”[65] To that end, Acheson urged the Senate that the North Atlantic Treaty, of which the Senate appeared skeptical, was essential to accomplishing this aim.[66]

After first addressing various foreign policy debates, Secretary Acheson provided a list of five points on which the executive and legislative branches agreed.[67] Again, these points of agreement concerned on foreign policy. First, Acheson asserted that both branches agreed on the “vital importance of a free Western Europe” to the security interests of the United States.[68] Second, the Secretary said that “there is no dispute concerning the basic principles underlying the North Atlantic Treaty.”[69] Third, both branches of government acknowledge the necessity of increasing the strength of the U.S. armed forces.[70] Fourth, there was general agreement between the Truman Administration and Congress that the primary aims of American foreign policy in Europe were to keep the U.S. out of war in Europe and to prevent one from breaking-out altogether.[71] Fifth and finally, the Secretary believed that there was general agreement that “we should send some additional troops to Europe to do our part in helping to build an integrated force, as one of the necessary deterrents to war.”[72]

From these points of agreement, Secretary Acheson addressed what he believed to be the core problem before the Joint Committee Hearing on S.R. 8. The Secretary did not think that presidential authority was the central issue. Rather, he thought that the central issue concerned “the amount, the manner, and timing of the build-up of our Ground Forces now in Europe in the interests of the security” of the United States.[73] Acheson narrowly tailored the issue presumably so as to focus his statement on his area of expertise: U.S. foreign policy. However, this narrowing of the issue suggests that Secretary Acheson did not question President Truman’s authority to unilaterally send troops to Europe. To Acheson, the president’s authority to take such an action was obvious.

Many senators took issue with Secretary Acheson’s lack of explanation concerning presidential authority, thereby prompting them to ask the Secretary for his thoughts directly. Senator Wiley, the first member of the Joint Committee to address the authority issue, asked the Secretary: “Under these circumstances, and I particularly stress ‘these circumstances,’ and considering the matter of the Atlantic Pact, would you care to comment as to the power of the Executive to send troops to Europe?”[74] Rather than fully answer the question, Secretary Acheson referred to a brief he had previously written and submitted to Congress on the issue.[75] Appearing in the Congressional Record on January 6, 1951 and reprinted in the record for the Joint Committee Hearing, Acheson’s brief addressed “the authority of the President to order the Armed Forces of the United States abroad for some purpose to which the United States is committed, including its security interests.”[76] While Secretary Acheson answered similar questions from other senators on the Joint Committee, Acheson’s January 6, 1951 brief provides the most comprehensive response to the issue of presidential authority. For this reason, Secretary Acheson’s brief is discussed in detail below.

Secretary of State Acheson asserted in his January 6, 1951 brief that the president possessed unique constitutional and precedential authority to send troops abroad. To that end, Acheson made the following three arguments: (1) the president can send troops abroad without congressional approval pursuant to the Commander-in-Chief power and the power to conduct the foreign relations of the United States; (2) the president has the power to faithfully execute the laws of the United States, which includes ratified treaties; and (3) past presidents have exercised their authority to send troops abroad on multiple occasions in the past without congressional approval.[77] These arguments all point to Secretary Acheson’s ultimate conclusion that President Truman had the inherent authority to send troops to Europe in furtherance of the North Atlantic Treaty.

First, Secretary Acheson argued that the president can send troops abroad without congressional approval pursuant to the Commander-in-Chief power and his power to conduct the foreign relations of the United States.[78] The Secretary effectively argued that as the Commander-in-Chief President Truman had the sole authority to send troops already raised by Congress wherever in the world he wished.[79] Further, Secretary Acheson asserted that the president’s duty to execute the foreign relations of the U.S. permitted the president to take any action necessary in furtherance of U.S. foreign policy interests, including sending troops abroad during times of peace.[80]

Here, it is important to note that Secretary Acheson, during the questioning period of his testimony to the Joint Committee, indicated that preserving the peace in Europe was expressly within the scope of U.S. foreign interests. Responding to a question from Senator Morse, Acheson explained that the U.S. has an express interest in protecting the lives and property of Americans abroad.[81] The Secretary specifically stated: “I can conceive of some things that are broader than the life of an American or the property of an American which would be the whole security of the United States, which might not involve the immediate life or the immediate property of someone in the field of action.”[82] The Secretary also conceded the following statements from Senator Morse regarding American foreign policy interests: “When we are moving in to protect American interests we are moving in to protect American security, however, in terms of either present danger to existing American lives or property interests, or future ones.”[83] Because protecting peace in Western Europe would protect future American lives and property abroad, Acheson believed that President Truman possessed the authority pursuant to his duty to execute the foreign relations of the U.S. to send troops to Europe in furtherance of the North Atlantic Treaty.

The Secretary cited explanations in favor of presidential power and authority during times of peace from Westel Willoughby and former-President William H.[84] Taft. Westel Willoughby explained in his constitutional law treatise that the president had the express and exclusive authority to send troops abroad during times of peace pursuant to the obligation to execute the foreign relations of the United States and, separately, the Commander-in-Chief power:

“As to his constitutional power to send United States forces outside the country in time of peace when this is deemed by him necessary or expedient as a means of preserving or advancing the foreign interests or relations of the United States, there would seem to be equally little doubt, although it has been contended by some that the exercise of this discretion can be limited by congressional statute. That Congress has this right to limit or to forbid the sending of United States forces outside of the country in time of peace had been asserted by so eminent an authority as ex-secretary Root. It would seem . . . however, that the President, under his powers as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, and his general control of the foreign relations of the United States, has this discretionary right constitutionally vested in him, and, therefore, not subject to congressional control.”[85]

Continually, the Secretary of State looked to the following argument made by former-President and former-Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States William Howard Taft in 1916.[86] Former-President Taft asserted that Congress could not infringe on the president’s power to send troops abroad:

“Two principles, limiting congressional interference with the Executive powers, are clear: First, Congress may not exercise any of the powers vested in the President, and second, it may not prevent or obstruct the use of the means given him by the Constitution for the exercise of those powers.”[87]

This argument is of particular significance because Taft engaged with the constitutional war power as a president, the Secretary of War to President Theodore Roosevelt, and a Supreme Court Justice.

Acheson also discussed failed attempts by Congress to limit, via military appropriations legislation, the president’s ability to move and send troops abroad to demonstrate the inherent authority of the president under the presidential war powers.[88] In 1912, Congress proposed an amendment to an army appropriations bill that would prevent the appropriation of money to U.S. Army troops stationed beyond the jurisdiction of U.S. laws.[89] If passed, this amendment would prevent the president from stationing troops abroad, thereby abrogating the president’s ability as Commander-in-Chief to move troops already raised wherever necessary. Similar amendments were also proposed to military appropriations bills in 1922 and 1928.[90] All three proposed amendments were defeated.[91]

Secretary Acheson used Senator Borah’s comments regarding the 1922 and 1928 proposed amendments, and their subsequent defeat, to clearly indicate congressional awareness that member of both the Senate and House of Representatives lacked the constitutional authority to limit the president’s Commander-in-Chief power.[92] Senator Borah argued during the debate over the 1922 limiting amendment that Congress could not interfere with the president’s rightful exercise of the Commander-in-Chief power, especially regarding the deployment and stationing of troops already raised.[93] Responding to a senator who asserted that Congress could compel the president to bring American troops back from abroad, Senator Borah stated:

“We could not make the President do it. He is Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy . . . and if in the discharge of his duty he wants to assign them there, I do not know of any power that we can exert to compel him to bring them home. We may refuse to create an army, but when it is created he is the commander.”[94]

Similarly, during the debate over the 1928 proposed appropriations bill amendment, Senator Borah argued that so long as the troops already exist, so long as Congress has raised them, the president may exercise the Commander-in-Chief power to send those troops wherever necessary to protect American interests.[95] According to the Senator, the Commander-in-Chief power and the president’s duty to execute the foreign relations of the U.S. together permit the president to send troops abroad without congressional permission. Furthermore, the Senator asserts that the president could send troops abroad even if there are not sufficient funds in the Treasury to execute this action.[96] Thus, as Senator Borah demonstrated, Congress recognized that the president possessed the sole and unimpeachable authority to send troops abroad, regardless of congressional approval of or even appropriation for such action.

Secretary Acheson discussed another episode in Congress when the Senate attempted to curtail the president’s war power and foreign relations authority to demonstrate congressional knowledge of the president’s sole control within these domains.[97] In 1919, the Senate considered ratifying the Treaty of Versailles.[98] A senator introduced a reservation to Article 10 of the treaty stating that Congress, under the Constitution, had “the sole power to declare war or authorize the employment of the military or naval forces of the United States.”[99] During debate on November 10, 1919, Senator Walsh of Montana opposed this reservation because it in fact misstated the war power granted to Congress.[100] The reservation’s claim that the Congress has the sole power to authorize use of the military was fundamentally false.[101] To that end, Senator Walsh stated:

“The whole course of our history has been a refutation of such a declaration, namely, that the President of the United States, the Chief Executive of the United States, the Commander in Chief of the Army of the United States, has no power to employ the land or naval forces without any express authorization upon the part of the Congress. Since the beginning of our Government, our Navy has been sent over the seven seas and to every port in the world. Was there ever any congressional act authorizing the President to do anything of that kind?”[102]

Senator Walsh went on to say that the U.S. Navy specifically ensures American interests abroad without challenge from Congress: “[O]ur Navy travels the sea ‘in order to safeguard and protect the rights of American citizens in foreign lands. Who can doubt that the President has no authority thus to utilize the naval and land forces of the United States?’”[103] To Senator Walsh and Secretary Acheson, the president’s authority in the realm of foreign policy was as clear as it was broad. Also, the president’s power to enact foreign policy went hand-in-hand with his power as the Commander-in-Chief to grant further credibility to any exercise of these powers.

Furthermore, Senator Borah of Idaho echoed Senator Walsh’s condemnation of the proposed reservation. To Senator Borah, not only was the reservation fundamentally false, but it served no purpose.[104] The language of the reservation could not change the division of the constitutional war powers to require congressional authorization of any military use.[105] That power belonged to the president per the Commander-in-Chief power.[106] As Borah put it, the inclusion of this reservation “would simply be vain and futile and, if I may say so, with due respect to those who drew it, the doing of an inconsequential thing.”[107] Congress simply did not possess the authority to claim this power nor could they abrogate the president’s war powers in this manner.

The Senate again debated the constitutional war powers in 1945, and Secretary Acheson included this debate in his January 6 1951 brief as another acknowledgement by Congress of the primacy of the president’s duty to conduct the foreign relations of the U.S.[108] During this debate, Senators Connally and Millikin indicated that presidents have engaged in a practice of sending troops abroad without the approval of Congress to protect United States foreign policy interests.[109] These Senators introduced a list of these instances, with particular focus on maintaining foreign interests in South America, to make their point.[110] For Secretary Acheson, Senators Connally and Millikin’s comments demonstrated congressional recognition of instances of past presidents executing the foreign relations of the United States by sending troops to protect American interests abroad.[111] Thus, Acheson asserted that Congress acknowledged that the president possesses the authority to send troops abroad without congressional approval to protect the country’s foreign policy interests.[112]

Secretary Acheson most clearly articulated his position on the core issue of the “Great Debate” in the January 6, 1951 brief when he quoted from a 1928 treatise entitled American Foreign Relations.[113] The author of this treatise, in reference to the 1919 debate discussed above, made the following statement: “[I]t is not true that, after raising forces and providing for their support, Congress can restrict the discretion of the President, as Commander in Chief, in directing their movements and in otherwise disposing of them.”[114] For the Secretary, the resolution to the “Great Debate” was this simple—Congress could not infringe on the president’s the Commander-in-Chief power because the troops had already been raised. Acheson’s other arguments merely lend further support this position.

Second, Secretary of State Acheson argued that President Truman had the authority to send troops to Europe in furtherance of the North Atlantic Treaty because he was obligated to do so pursuant to the presidential duty to take care that the laws are faithfully executed. Because ratified treaties become law, Acheson asserted that the president is specifically empowered to take any action necessary to ensure that the terms of such treaties are faithfully executed.[115] As former-President and former-Chief Justice of the Supreme Court William H. Taft explained, “The duty that the President has to take care that the laws be faithfully executed applies not only to the statutory enactments of Congress but also to treaties . . . .”[116] For Secretary Acheson, President Truman’s decision to send troops to Europe was justified as a necessary measure to faithfully execute the North Atlantic Treaty, and Congress could not infringe on this exercise of presidential power.

In furtherance of this position, Acheson identified discussions in the Congressional Record where senators specifically addressed the power of the president to enact the treaties that the Senate debated ratifying. For example, Acheson examined the Senate debate over the approval of the Charter of the United Nations.[117] The Secretary first cited the Senate’s discussion over the issue of distinguishing whether the UN Charter would function as an “agreement” or a treaty.[118] According to Senator Wiley, the distinction effectively would not matter when it came to the charter’s implementation:

“It is my understanding, according to the testimony given before the Foreign Relations Committee of the Senate that the terms ‘agreement or agreements’ as used in article 43 are synonymous with the word ‘treaty.’ On the other hand, I recognize that Congress might well interpret them as agreements brought about by the action of the Executive and ratified by a joint resolution of both Houses. These agreements would provide for a police force and the specific responsibility of each nation. But outside of these agreements, there is the power in our Executive to preserve the peace, to see that the ‘supreme laws’ are faithfully executed. When we become party to this charter, and define our responsibilities by the agreement or agreements, there can be no question of the power of the Executive to carry out our commitments in relation to international policing. His constitutional power, however, is in no manner impaired.”[119]

For Senator Wiley, there was no question that ratifying the charter would create a presidential obligation to execute its terms. Furthermore, Senator Wiley indicated that Congress could not infringe on the president’s authority to do so.

Secretary Acheson then pointed to comments in this same Senate debate made by Senator Austin, directly addressing the presidential obligation to take care that the laws are faithfully executed in relation to treaties.[120] Senator Austin believed that the general powers of the president, including but not limited to the presidential war powers, are all “commensurate with” the obligation to take care that the laws are faithfully executed.[121] “That means,” the Senator explained, “that [the president] shall take all the care that is required to see that the laws are faithfully executed.”[122] Senator Austin argued that the president possessed the authority to take any action necessary to fulfill this obligation, including sending troops, without any interference from Congress, so long as such action was indeed necessary to faithfully execute the law.[123] To that end, Senator Austin stated:

“Of course, there are other specific references in the Constitution which show that he has the authority to employ armed forces when necessary to carry out specific things named in the Constitution; but the great over-all and general authority arises from his obligation that he take care that the laws are faithfully executed. That has been true throughout our history, and the Chief Executive has taken care, and has sent the Armed Forces of the United States, without any act of Congress preceding their sending, on a great many occasions. . . . But there is no doubt in my mind of his obligation and authority to employ all the force that is necessary to enforce the laws.”[124]

Senator Austin also addressed whether the obligation to faithfully execute the laws of the United States extends to treaties. Answering this question in the affirmative, Senator Austin made the following statement:

“It may be asked, How does a threat to international security and peace violate the laws of the United States? Perhaps, Mr. President, it would not have violated the laws of the United States previous to the obligations set forth in this treaty. . . . We recognize that a breach of the peace anywhere on earth which threatens the security and peace of the world is an attack upon us: and after this treaty is accepted by 29 nations, that will be the express law of the world. . . . [I]t will be the law of the United States, because we shall have adopted it in a treaty. Indeed, it will be above the ordinary statutes of the United States, because it will be on a par with the Constitution, which provides that treaties made pursuant thereto shall be the supreme law of the land.”[125]

Senator Austin argued that the Constitution vested the responsibility to maintain peace on the president alone.[126]

Thus, employing the above statements from Senators Wiley and Austin, Secretary Acheson argued in his January 6, 1951 brief that President Truman possessed the exclusive authority to send troops abroad to maintain the North Atlantic Treaty per his obligation to take care that the laws of the United States are faithfully executed.

Third, Secretary Acheson demonstrated that President Truman’s decision to send troops without congressional approval was not novel. Throughout his January 6, 1951 brief, Acheson cited instances of former presidents taking similar unilateral action to send troops abroad.[127] These examples are discussed below. Note that Acheson’s brief also mentioned several lists that purport to provide every instance in which a president sent troops abroad without express approval from Congress.[128] Two of these lists provided approximately 70 examples, while another counted 150 examples.[129] Referencing these lists allowed the Secretary to lend further credit to his claims that other presidents have unilaterally sent troops abroad before, and it is a uniquely presidential act.

The Secretary of State used the following examples of similar presidential actions and any subsequent response by Congress as a key feature of his overall argument in favor of presidential authority. Secretary Acheson first discussed the U.S.’s involvement in the Boxer Rebellion in China (1900 to 1901). As Secretary Acheson described the situation, “the President sent about 5,000 troops to join with the British, Russian, German, French, and Japanese troops to relieve the siege of the foreign quarters in Peking and reestablish the treaty status. This was done without express congressional authority.”[130] For the Secretary, this troop deployment demonstrated a lawful exercise of the president’s Commander-in-Chief power, a necessary action to enact the foreign relations of the United States, and a necessary action to faithfully execute and maintain an international treaty.

In particular, Secretary Acheson focused on the argument then-Secretary of State John Hay made in favor of the president’s authority to send troops to China during the Boxer Rebellion. Hay argued the following:

“The purpose of the President is, as it has been heretofore, to act concurrently with the other powers; first, in opening up communications with Peking and rescuing the American officials, missionaries, and other Americans who are in danger; secondly, in affording all possible protection everywhere in China to American life and property; thirdly, in guarding and protecting all legitimate American interests; and, fourthly, in aiding to prevent a spread of the disorders to the other provinces of the Empire and a recurrence of such disasters. It is, of course, too early to forecast the means of attaining this last result; but the policy of the Government of the United States is to seek a solution which may bring about permanent safety and peace to China, preserve Chinese territorial and administrative entity, protect all rights guaranteed to friendly powers by treaty and impartial trade with all parts of the Chinese Empire.”[131]

Then-Secretary Hay asserted that America had a vested interest in protecting American lives and property, ensuring stability in the region, and reestablishing the foreign quarters in Peking.[132] Hay believed that the president could take whatever action necessary to fulfill these interests per the president’s duty to enact U.S. foreign policy.[133] And, again, the president took this action without input from Congress. Thus, Secretary Acheson cited Hay’s justification to lend further credit to his argument in favor of presidential authority to send troops abroad without congressional approval.

Next, Acheson discussed the decision to send naval forces to Iceland and other islands at the beginning of World War II as another example of the exercise of the presidential Commander-in-Chief and foreign relations powers. On July 7, 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (“FDR”) informed Congress that he was exercising the Commander-in-Chief power to send naval forces to Iceland, Trinidad, and British Guiana.[134] FDR gave two reasons for these deployments. First, the United States need to ensure “the safety of communications between Iceland and the United States as well as on the seas between the United States and all other strategic outposts.[135] Sending troops was necessary to achieve this military initiative.[136] Second, the United States had a vested interest in protecting itself and the Western Hemisphere against potential air or naval attacks from Germany, which could be executed more easily from strategic outposts in the Atlantic.[137] Thus, it was necessary to send troops to Iceland, Trinidad, and British Guiana to protect the safety of the United States.[138]

While FDR specifically invoked the Commander-in-Chief power, Secretary Acheson also employed this historical precedent as an example of the president using troops to execute the foreign policy of the United States.[139] In July 1941, the United States had not yet declared war on either Japan or Germany. However, FDR sent troops abroad without the express approval of Congress.[140] FDR’s reasons for sending troops abroad therefore appeared to constitute American foreign policy interests, not military ones. For this reason, Acheson employed FDR’s actions as examples of a president properly and unilaterally sending troops abroad pursuant to both the Commander-in-Chief power and the president’s duty to enact the foreign relations of the United States.

Similarly, Secretary of State Acheson discussed the president’s response to the Samoan civil war in 1888 and 1889 as an example of a president ensuring the laws (including treaties) are faithfully executed.[141] Prior to the outbreak of the Samoan civil war, the United States, Great Britain, and Germany entered into treaties that granted each nation the right to maintain naval depots in the region.[142] During the civil war, however, Germany sent military forces to Samoa to protect their treaty rights and restore peace to the islands, and they invited the United States to join in this effort.[143] The U.S. agreed and sent troops to Samoa.

To better understand the reason for this action, Acheson referred to the Secretary of the Navy’s instructions to the commander of the United States naval forces in the Pacific about moving troops to Samoa. The Secretary of the Navy gave the naval commander the following instructions:

“He [the commander of U.S. naval forces in the Pacific] was to extend full protection and defense to American citizens and property, to protest the displacement of the native government by Germany as violating the positive agreement and understanding between the treaty powers, but to inform the British and German Governments of his readiness to cooperate in causing all treaty rights to be respected and in restoring peace and order on the basis of the recognition of the Samoan right to independence.”[144]

Furthermore, the Secretary of the Navy explained that the U.S. “was willing to cooperate in restoring order ‘on the basis of the full preservation of American treaty rights and Samoan authority, as recognized and agreed to by Germany, Great Britain, and the United States.’”[145] Thus, for Secretary Acheson, this historical event stood as an example of the executive branch exercising their power to faithfully execute the laws of the United States, of which treaties also constitute the law. The president could and did validly send troops to Samoa pursuant to this specific power under the Constitution.

As the final example, Secretary Acheson discussed how Presidential Theodore Roosevelt’s decision to send troops to Cuba per the Platt Amendment demonstrated an instance of a president executing the foreign relations and the laws of the U.S.[146] The Platt Amendment, which was attached as a rider to the Army Appropriations Bill of 1901, functioned as a treaty between the U.S. and Cuba following the Spanish American War to ensure Cuban independence and “the maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, property, and individual liberty.”[147] To achieve these goals, the amendment granted the U.S. considerable power to, among other things, intervene in Cuban internal affairs.[148] Secretary Acheson referred to an instance in which the Theodore Roosevelt Administration sought to oust Cuban President Palma’s government for acting contrary to these principles.[149]

As Former-President Taft, who served as Secretary of War to President Roosevelt at the time, articulated, “the question was whether the President, without action by Congress, could use the Army and Navy and intervene under the so-called Platt amendment of the treaty between Cuba and the United States.”[150] Secretary Acheson focused on the advice that Taft gave to President Roosevelt in answering this question. Taft stated:

“I advised the President that this treaty, pro tanto, extended the jurisdiction of the United States to maintain law and order over Cuba in case of threatened insurrection, of danger of life, property, and individual liberty, and that under his duty to take care that the laws be executed this was ‘a law’ and his power to see that it was executed was clear.”[151]

Taft effectively informed the President that he could take whatever action necessary to enforce the Platt Amendment as a core function of the president’s duty to execute the laws of the United States, including sending military troops to the island nation, without congressional approval. As a result, President Roosevelt sent troops to Cuba to restore order, institute a provisional government, conduct a fair election, and install the newly elected government.[152]

Acheson also made sure to note Congress’ response to President Roosevelt’s troop deployment in this matter. Although the Senate clearly opposed this presidential action, they did not adopt a resolution to officially condemn it.[153] Rather, Congress appropriated the money necessary to support troops sent to Cuba.[154] Congress also “recognized the provisional government in Cuba in such a way as to make the course taken a precedent.”[155] Thus, Congress tacitly approved the use of troops in Cuba as an appropriate measure to enforce the Platt Amendment. Secretary Acheson employed this example as a clear demonstration of presidential authority to use troops to enforce the laws (and treaties) of the United States.

Finally, note that Secretary Acheson did answer Senator Wiley’s question aside from referencing his January 6, 1951 brief.[156] In response to the question of whether President Truman had the authority to send troops to Europe, the Secretary stated:

“It seems to me that that is clearly established both by court decisions and by an unbroken practice from the very first days of the Republic. It seems to me that perhaps a little more is involved here, and that we are in a position in the world today where the argument as to who has the power to do this, that, or the other things, is not exactly what is called for from America in this very critical hour, and if we could all agree on the fact that something should be done, we will perform a much greater role in the world, than by quarreling about who ought to do it.”[157]

Secretary Acheson clearly believed that presidential authority was a nonissue here. While the Senate was concerned that President Truman had infringed on their constitutional war powers in some way, the Secretary of State argued that the President alone possessed the power to take this action. Furthermore, the tone of Acheson’s response indicates that he thought that this debate was irrelevant and distracted from the actual issue at hand—defeating the Soviet Union and stopping the spread of Communism.

It is worth noting that, given his statements discussed above from the ratification debates over the Charter of the UN, Senator Wiley may have believed that the President did possess the sole authority to send troops to Europe in support of NATO. This would appear likely because, after asking this question, the Senator did not press Secretary Acheson on the issue. Rather, he responded to Acheson’s answer by saying, “I agree fully with that conclusion, Mr. Secretary. . . .”[158] Senator Wiley continued:

“. . . [B]ut I do think that we here sitting as a committee of the Senate, a joint committee, are called upon, in view of the very precedent that you have in mind, to distinguish what our field of activity is and what the field of the President is. Then if there is any conflict, in the public interest, that the two get together and harmonize perhaps in the public interest their respective fields of activity.”[159]

As Wiley’s comments from the Hearing and from the Congressional Record in 1945 indicated, he understood that there was a clear distinction in the constitutional grant of powers between the president and Congress at issue in the “Great Debate.”[160] By asking the question and making his subsequent statements, Senator Wiley appeared to flag the issue of clearly delineating between these constitutional grants of power for the Joint Committee. Ultimately, this lent further credit to Secretary Acheson’s arguments, especially given that the adopted version of S.R. 8 approved Truman’s initial troop announcement from December of 1950.[161]

Ultimately, Secretary Acheson argued to the Joint Committee Hearing that President Truman possessed unquestionable and uninfringeable authority to send ground forces to Europe in support of the North Atlantic Treaty. By not discussing the issue of constitutional authority in his opening statement to the Joint Committee, Secretary of State Acheson impliedly argued that the president clearly had the requisite authority alone to send these troops abroad. And, when asked to explain where this obvious authority came from, Acheson pointed to the arguments he made in favor of presidential power in his January 6, 1951 brief. The arguments in this brief merely granted further support his unstated conclusion. Articulating this position, Acheson wrote:

“Not only has the President the authority to use the Armed Forces in carrying out the broad foreign policy of the United States and implementing treaties, but it is equally clear that this authority may not be interfered with by the Congress in the exercise of powers which it has under the Constitution.”[162]

- Conclusion

While the “Great Debate” concluded with the adoption of S.R. 8, the arguments that Secretary of State Dean Acheson made during the Joint Committee Hearing in favor of presidential authority to send troops abroad without congressional approval persist to this day. Acheson made three affirmative arguments in his January 6, 1951 brief referenced and reprinted in the Hearing’s record. First, he argued that the president can send troops abroad without congressional approval pursuant to the Commander-in-Chief power and the power to conduct the foreign relations of the United States. Second, Acheson explained that the president has the power to faithfully execute the laws of the United States, which includes ratified treaties. Under these two arguments, Acheson explained that not only could President Truman unilaterally send troops abroad pursuant to one of these three grants of power, but Congress could not rightfully interfere. Third, the Secretary asserted that President Truman’s actions were not novel and that there was past precedent to support the President’s authority to take such action. Ultimately, however, Acheson made his most resounding argument in his opening statement to the Joint Committee Hearing: by not discussing constitutional authority at all, Acheson implied that President Truman possessed unquestionable authority to send troops to Europe in support of NATO without approval from Congress.

Whether or not the “Great Debate” was truly great, Congress grappled with the new reality of international relations and the United States’ new position on the world stage.[163] And they attempted to reconcile the demands of this new reality with the parameters of the war powers under the Constitution. As they discovered, the new reality necessarily required the nation’s leaders to reframe their understanding of the war powers in combination with the international treaties that they had drafted, negotiated, and ratified. It is the arguments which fused constitutional war powers with the provisions of the mutual defense pacts that remain relevant and in use today.

Constantine Rodriguez, J.D.

AuthorConstantine Rodriguez is a recent graduate of Tulane Law School. She received her undergraduate education at the University of Notre Dame, where she studied history with a concentration in modern state building. She now works as an associate at Hinshaw & Culbertson in their New Orleans office.

[1] Raymond P. Ojserkis, Beginnings of the Cold War Arms Race: The Truman Administration and the U.S. Arms Build-Up118 (Praeger 2003) (citing Herbert Hoover, “Our National Policy In This Crisis,” speech given December 20, 1950, in Vital Speeches of the Day 165-67 (1951)).

[2] Ojserkis, supra note 1, at120.

[3] See Matthew Waxman, Chapter 8 draft 15-16 (2023).

[4] See Id., at 16-18.

[5] Id., at 16.

[6] The President’s News Conference, The American Presidency Project (last visited Nov. 27, 2023), https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-news-conference-567.

[7] Foreign Relations of the United States 1951, H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 22 (1981) (citing Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Harry S. Truman, 1951 at 19 (1965)).

[8] Ojserkis, supra note 1, at118 (citing Herbert Hoover, “Our National Policy In This Crisis,” speech given 20 December 1950, Vital Speeches of the Day 165-67 (January 1, 1951)).

[9] Id.

[10] Id., at 120

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] See Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952). This case is the leading US Supreme Court case contemplating the scope of presidential power. This case challenged President Truman’s ability to stop a workers’ strike in the steel industry by commandeering the industry for the Vietnam war effort. The only aspect of the majority decision that matters in modern constitutional law is the decision that it was unconstitutional for the president to take such an action, as it does not fall within president’s power per the Article II of the Constitution. Justice Jackson’s concurring opinion in the case (and to a lesser extent Justice Frankfurter’s concurring opinion) provides the most guidance as to evaluate presidential decisions and presidential power. Justice Jackson’s opinion states the following: presidential actions fall into one of three categories. When the president takes an action that is consistent with an act of Congress, he is at the height of his power. When the president takes an action and Congress is silent, he is in a sort of “middle bucket.” He must rely on the Constitution alone for justification and legitimization. Finally, when the president acts contrary to an act of Congress, he is at his weakest. The president must find some justification in the Constitution or else his action is expressly vulnerable to Congressional override. It is notable that presidential action in the realms of international diplomacy and military decisions will almost always fall into the second category because such decisions, per the Constitution, are the exclusive power of the president.

[14] Ojserkis, supra note 1, at 121-22; see Waxman, supra note 3, at 16, 18; Matthew Waxman, NATO and War Powers: Remember the ‘Great Debate’ of the 1950s, Lawfare (July 11, 2018), https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/nato-and-war-powers-remembering-great-debate-1950s;

[15] H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 23.

[16] SeeWaxman, supra note 3, at 1-2, 16.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id., at 2.

[21] Waxman, supra note 3, at 2.

[22] Louis Fisher, Presidential War Power 105-06 (Univ. Press of Kansas, 2d ed., rev. 2004); see Stephen M. Griffin and Matthew C. Waxman, War Powers: Congress, the President, and the Courts — A Model Casebook Section 3, 11-13 (Columbia Public Law Research Paper No. 14-669, Tulane Public Law Research Paper No. 20-18, 2020), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3692831.

[23] Fisher, supra note 22, at105-06.

[24] See Waxman, supra note 3, at 14.

[25] Assignment of Ground Forces of the United States to Duty in the European Area: Hearings on S. Res. 8 before the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels. and S. Comm. on Armed Servs., 82d Cong. 78 (1951) [hereinafter Hearings] (statement of Secretary of State Dean Acheson).

[26] See Waxman, supra note 3, at 14.

[27] North Atlantic Treaty art. 3, April 4, 1949, 63 Stat. 2241, 34 U.N.T.S 243.

[28] North Atlantic Treaty art. 5, April 4, 1949, 63 Stat. 2241, 34 U.N.T.S 243.

[29] Fisher, supra note 22, at 107 (citing North Atlantic Treaty art. 5, April 4, (1949); U.N. Charter art. 51).

[30] Id., at 105 (citing North Atlantic Treaty (1949)).

[31] Id., at 106-07 (referencing North Atlantic Treaty art. 11 (1949)).

[32] Id., at 107 (citing North Atlantic Treaty (part 1): Hearings on the North Atlantic Treaty before the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels., 81st Cong. 11 (1949)).

[33] Id. (citing North Atlantic Treaty (part 1): Hearings on the North Atlantic Treaty before the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels., 81st Cong. 11 (1949)).

[34] Fisher, supra note 22, at 107-08 (North Atlantic Treaty (part 1): Hearings on the North Atlantic Treaty before the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels., 81st Cong. 11 (1949)).

[35] Fisher, supra note 22, at 105; Waxman, supra note 3, at 4.

[36]Waxman, supra note 3, at 3-6.

[37] Fisher, supra note 22, at 81.

[38] Waxman, supra note 3, at 4.

[39] Ojserkis, supra note 1, at 118 (citing Herbert Hoover, Our National Policy In This Crisis speech given 20 Dec. 20, 1950, in Vital Speeches of the Day at 165-67 (Jan. 1, 1951)).

[40] Waxman, supra note 3, at 16.

[41] Id.

[42] Waxman, supra note 3, at 2.

[43] H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 22.

[44] Waxman, supra note 3, at 16.

[45] Foreign Relations of the United States 1951, H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 22 (1981).

[46] H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 24 (citing S.R. 99, 82d Cong. (1951); S. Rep. No. 82-175). Note that, upon its rewrite and report out of committee, the Senate changed the name of S.R. 8 to Senate Resolution 99. See Id. For the purposes of this essay, we will continue to refer to this resolution as S.R. 8.

[47] Fisher, supra note 22, at 114 (citing 97 Congressional Record 3082-83, 3095-96 (1951)).

[48] H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 24; 97 Cong. Rec. 94 (1951).

[49] Id.; see also Fisher, supra note 22, at 113-14 (citing 97 Cong. Rec. 3082-83, 3095-96 (1951)).

[50] Fisher, supra note 22, at 114 (citing 97 Cong. Rec. 3199 (1951)).

[51] H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 24; Ojserkis, supra note 1, at 122.

[52] Ojserkis, supra note 1, at 122.

[53] Id.

[54] Fisher, supra note 22, at 113.

[55] Matthew Waxman, NATO and War Powers: Remember the ‘Great Debate’ of the 1950s, Lawfare (July 11, 2018), https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/nato-and-war-powers-remembering-great-debate-1950s.

[56] See Hearings, supra note 22, at 77-125.

[57] H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 23.

[58] See Hearings, supra note 22, at 77-125; Foreign Relations of the United States 1951, H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 23 (1981).

[59] See Hearings, supra note 22, at 77-125.

[60] See Id.

[61] Id., at 88.

[62] Foreign Relations of the United States 1951, H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 23 (1981).

[63] See Hearings, supra note 22, at 77-86.

[64] Id.

[65] Hearings, supra note 22, at 78.

[66] Id., at 82.

[67] Id., at 84.

[68] Id.

[69] Id.

[70] Hearings, supra note 22, at 84.

[71] Id.

[72] Id.

[73] Id., at 84.

[74] Id., at 88.

[75] 97 Cong. Rec. 933 (1951) [hereinafter The Brief] reprinted in Assignment of Ground Forces of the United States to Duty in the European Area: Hearings on S. Res. 8 before the S. Comm. on Foreign Rels. and S. Comm. on Armed Servs., 82d Cong. 88-93 (1951) (statement of Secretary of State Dean Acheson); Hearing, supra note 25, at 88.

[76] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 88.

[77] See The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 88-93.

[78] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 88-90.

[79] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 88-93.

[80] Id.

[81] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 123-24.

[82] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 123.

[83] Id.

[84] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing Westel Willoughby, The Constitutional Law of the United States 1567 (vol. III 1929); William H. Taft, Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers 126 (1916)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 89, 92.

[85] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing Willoughby, supra note 84, at 1567); Hearing, supra note 25, at 89.

[86] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing Taft, supra note 84, at 126); Hearing, supra note 25, at 92.

[87] Id.

[88] See The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 48 Cong. Rec. 10921-30 (1912); 63 Cong. Rec. 933 (1922); 69 Cong. Rec. 6744-62, 6843-48 (1928)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[89] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 48 Cong. Rec. 10921-30 (1912)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[90] Id.

[91] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 48 Cong. Rec. 10921-30 (1912); 63 Cong. Rec. 933 (1922); 69 Cong. Rec. 6744-62, 6843-48 (1928)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[92] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[93] Id.

[94] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 63 Cong. Rec. 933 (1922)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[95] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 69 Cong. Rec. 6744-62, 6843-48 (1928)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[96] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 69 Cong. Rec. 6760 (1928)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[97] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 58 Cong. Rec. 8195 (1919)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 89.

[98] Id.

[99] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 58 Cong. Rec. 8195 (daily ed. Nov. 10, 1919) (statement of Sen. Lodge)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 89.

[100] Id.

[101] Id.

[102] Id.

[103] Id.

[104] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 58 Cong. Rec. 8195 (daily ed. Nov. 10, 1919) (statement of Sen. Lodge)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 89.

[105] Id.

[106] Id.

[107] Id.

[108] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[109] Id.

[110] Id.

[111] Id.

[112] See Id.

[113] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing Matthews, American Foreign Relations 553 (1928)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 89-90.

[114] Id.

[115] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 90-91.

[116] The Brief, supra note 72 (quoting William Howard Taft, The Boundaries Between the Executive, the Legislative, and the Judicial Branches of Government, 25 Yale L. J. 613); Hearing, supra note 25, at 90-91.

[117] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 91-92.

[118] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 91.

[119] The Brief, supra note 72 (emphasis added); Hearing, supra note 25, at 91; 91 Cong. Rec. 8127-28 (daily ed. July 27, 1945) (statement of Sen. Wiley).

[120] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 79 Cong. Rec. 8064-65 (daily ed. July 26, 1945) (statement of Sen. Austin)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 91.

[121] Id.

[122] Id.

[123] Id.

[124] Id.

[125] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 79 Cong. Rec. 8064-65 (daily ed. July 26, 1945) (statement of Sen. Austin)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 91-92.

[126] Id.

[127] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[128] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing Cong. Rec. Appendix A (1941)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[129] Id.

[130] Id.

[131] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing V Moore’s Digest of International Law 482 (n.p. n.d.); see also Taft, supra note 84, at 114-15; James Grafton Rogers, World Policing and the Constitution, in World Peace Foundation 58-62 (1945); Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[132] Id.

[133] Id.

[134] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 87 Cong. Rec. 5868 (daily ed. July 7, 1941) (statement by President Franklin D. Roosevelt)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[135] Id.

[136] Id.

[137] Id.

[138] Id.

[139] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[140] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 87 Cong. Rec. 5868 (daily ed. July 7, 1941) (statement by President Franklin D. Roosevelt)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[141] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 90.

[142] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing I Moore’s Digest of International Law 545-46 (n.d.)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 91.

[143] Id.

[144] Id.

[145] Id.

[146] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 92.

[147] The Brief, supra note 72 (citing Taft, supra note 84, at 613-14); Hearing, supra note 25, at 92; Platt Amendment (1903), National Archives (last viewed Nov. 25, 2023), https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/platt-amendment.

[148] Id.

[149] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 92 (citing Taft, supra note 84, at 613-14).

[150] Id.

[151] Id.

[152] Id.

[153] Id.

[154] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 92 (citing Taft, supra note 84, at 613-14).

[155] Id.

[156] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 93.

[157] Id.

[158] Id.

[159] Id.

[161] See Foreign Relations of the United States 1951, H.R. Doc. No. 82-570, vol. III at 24 (1981) (citing S. Rep. No. 82-175 (1951). Note that, upon its rewrite and report out of committee, the Senate changed the name of S.R. 8 to Senate Resolution 99.

[160] See The Brief, supra note 72 (citing 91 Cong. Rec. 8064-65 (daily ed. July 26, 1945) (statement by Senator Wiley)); Hearing, supra note 25, at 91.

[162] The Brief, supra note 72; Hearing, supra note 25, at 92.

[163] See Robert David Johnson, Congress and the Cold War 50-52 (Cambridge Univ. Press 2006).

Constantine Rodriguez clearly and thoughtfully explores Secretary of State Dean Archeson’s argument in favor of President Truman’s authority to station troops in peacetime Europe during the “Great Debate” of 1951. Rodriguez’s excellent prose is academic yet easy to read; she tackles the complexities of the US legal system in a way that non-experts can understand. Her article is divided into three parts: a well-written background on the beginnings of the Cold War and the various understandings of presidential power, a discussion of Senate Resolution 8 and the opponents of presidential authority to deploy peacetime troops without Congressional approval, and, the core of her essay, Secretary Archeson’s response. Rodriguez’s critical analysis is the strongest part of the paper; she argues that Archeson communicates presidential authority by omitting the argument entirely from his opening statement. Similarly, she highlights the nuances of Archeson’s citations of Taft and FDR. Since Rodriguez’s article is a legal essay, it includes frequent long citations. Historical essays generally prioritize paraphrasing or summarizing over direct quotations — except in the case of analyzing the direct quotation. Rodriguez also slips into informal colloquialisms (e.g., “begged to differ”) and can be repetitive at times. However, these faults are outshone by her clear voice and excellent understanding of US Cold War politics. Overall, Rodriguez excellently demonstrates how the presidential authority to deploy troops became an integral part of the Cold War.